About Rachel

Leaving home

When I left home to go to university (with a childhood steeped in sadnesses that I preferred not to think about) I owned a small suitcase of bits and pieces from my family’s past – photos, love letters, diaries, book marks, old shoes, locks of hair, sheet music, knitting needles – and an awful lot of stories. And that was all.

Later on during the time when I was working in museums (I ran a museum-making company called Metaphor with my partner Stephen Greenberg) I kept my family’s stuff in boxes under our double bed in the attic, and in most of those years I didn’t even look inside them. But then

one day we were moving house and so I knelt on the attic floor and pulled out the boxes. When I saw their contents I realised that in what we do with our memories and the stuff our parents leave behind – we are all museum-makers.

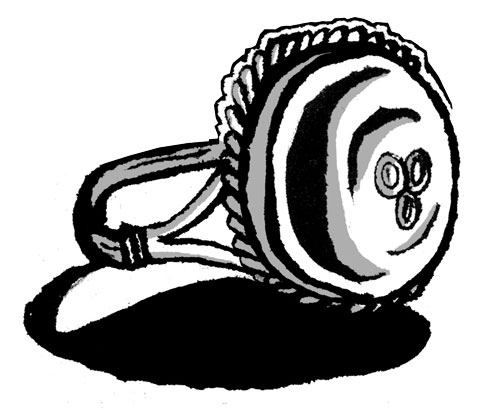

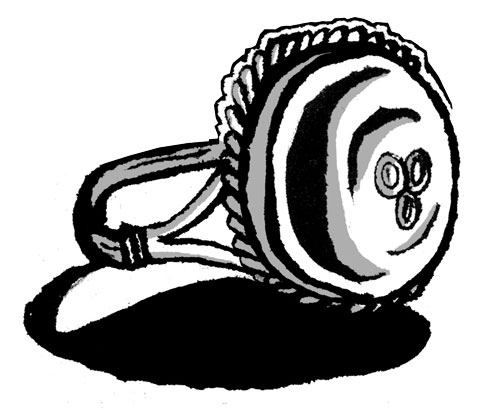

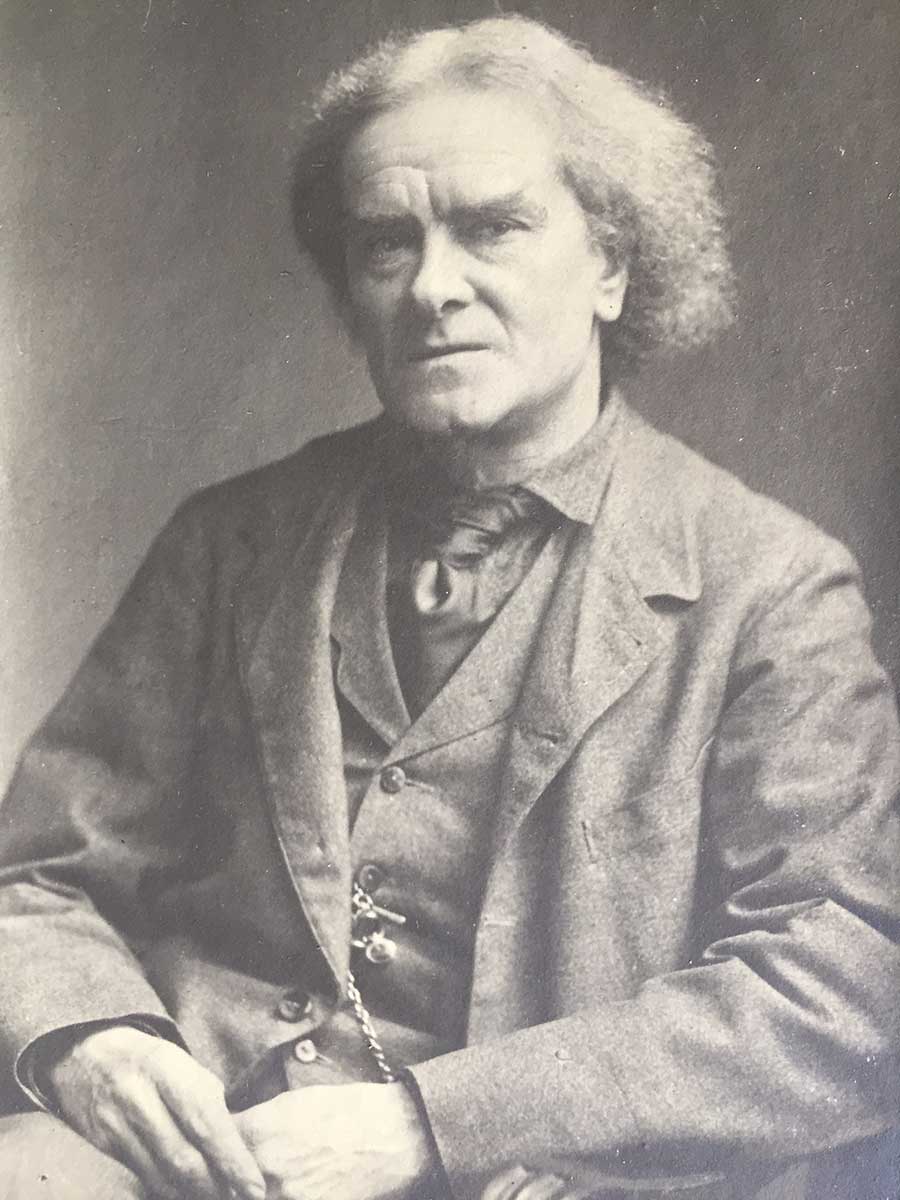

Museums are as much boxes of stories as they are boxes of things. A thing without a story (who made it, owned it, used it, loved it, stole it) is only half a thing – because stories make things more compelling, although things also lend credence to stories and say yes, that really happened because here’s the thing to prove it. Amongst the things in the boxes under the bed was a Victorian ring. It had belonged to my great-great-grandfather, who had been a notorious Victorian Free Lover and whose behaviour had brought down an avalanche of scandal and trouble on the family. The consequences of scandals often echo down the generations. That, said Gran, was the way it had been for us.

Keep them safe

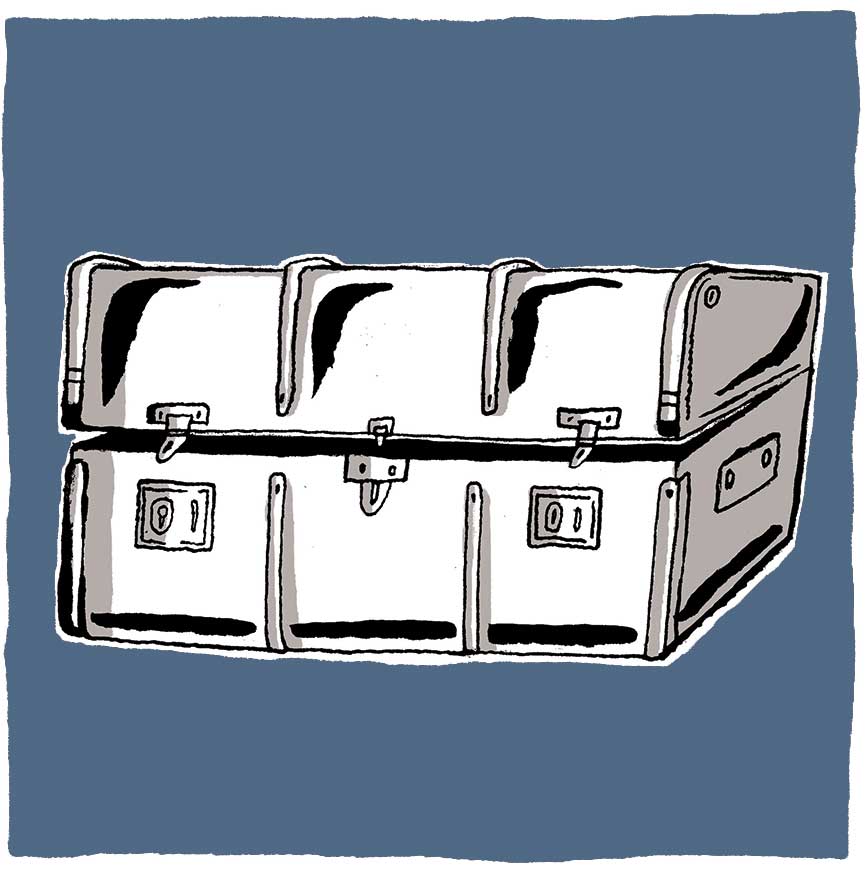

Things also need somewhere to keep them safe. By now I was starting to make a museum of my family. I didn’t have showcases or museum buildings of course, but I did have an old tin trunk, painted green and with a curved lid, which had come down from my great-grandfather’s side of the family. That was the beginning of the Museum of Me.

And things also need ways to keep them connected to their stories. (I knew from my museum work how easily they fly apart.) It was partly for this reason that I began to make a catalogue of my museum which then developed into my book, The Museum Makers, which is part history of museums, part family history, part how-to-make-a-museum handbook, and part meditation on time and memory and the stories families tell.

So why did I do this?

For three reasons. If museums are about how to make order out of chaos then the part of me that was still a baffled child was now using the things in the boxes under the bed to try to make sense of my past. Museum-making is a therapeutic process.

I also felt some odd sense of loyalty to those ancestors of mine, even the ones who had behaved badly, but especially the ones who, I thought, had been unfairly forgotten.

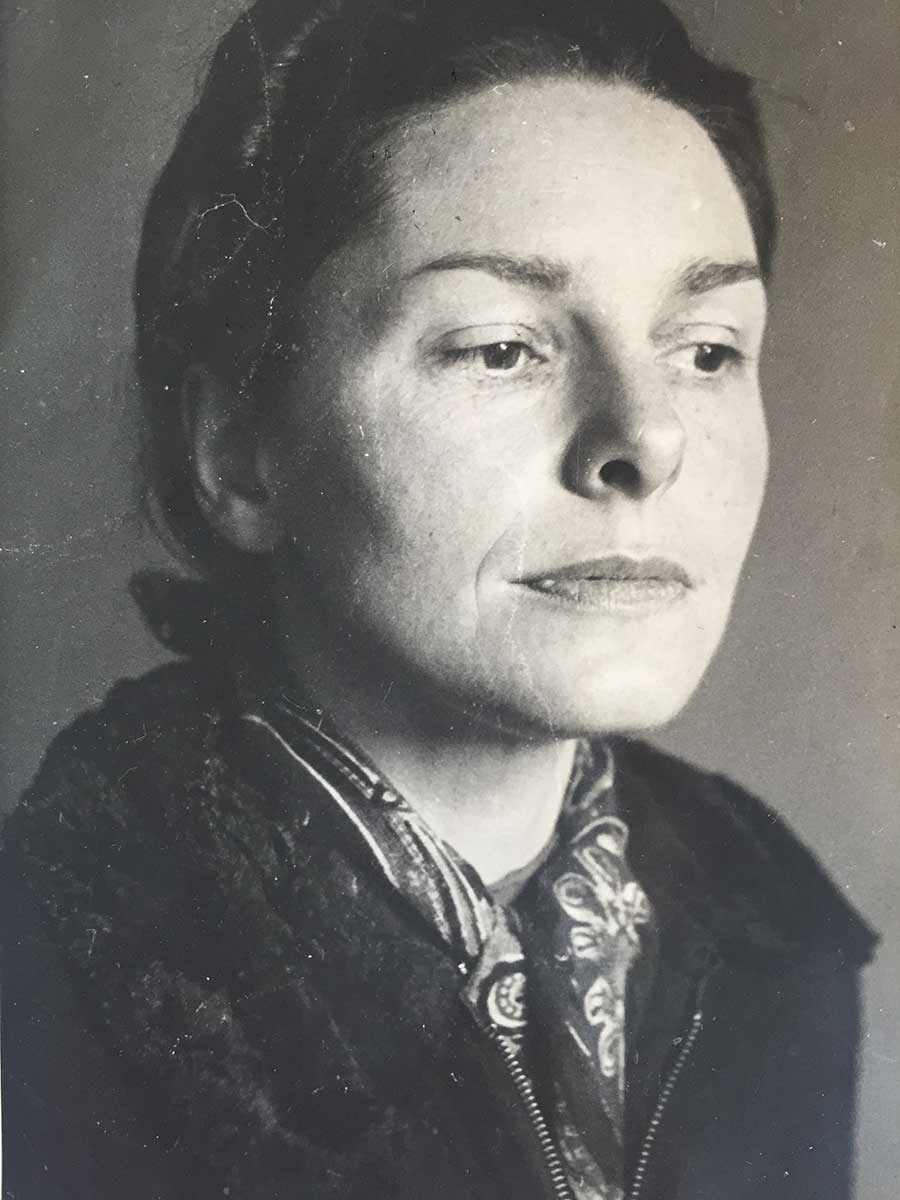

But my biggest motive for writing the book was to remember Gran; not that we had ever forgotten her but it still bears repeating that Gran was amazing. She fished my two brothers and me out of the chaos of our parents’ marriage and brought us up on her state pension. I loved Gran very much, though she was very strong-willed, she wasn’t easy. She came from an Edwardian literary and bohemian family, had married young, and went to New Zealand, divorced, and brought up her two girls by writing romantic novels. She took six weeks to write each one of them, put them on the boat to England and wrote another one straight away so it would be ready when the next boat arrived. I think grandmothers are often under estimated. In a way my book became a hymn to all grandmothers everywhere.

So what did I learn from writing the book?

I learnt all kinds of things, about time and memory and museum-making – all of which I put into the book – though maybe most of all I learnt never to throw away the past and always to listen to your grandma’s stories.