Sometimes an idea strikes you with such freshness and force that you think you are the first person in the world ever to have it. It’s never true of course.

I had one of those moments one summer when we were packing up to move house and I was sorting boxes of old family stuff that had been abandoned for years under our bed. It was a time when I was deeply involved in our museum-making company. All those years of making exhibitions had taught me that museum-making is about laying out things to make meaningful patterns out of the confusions of the world.

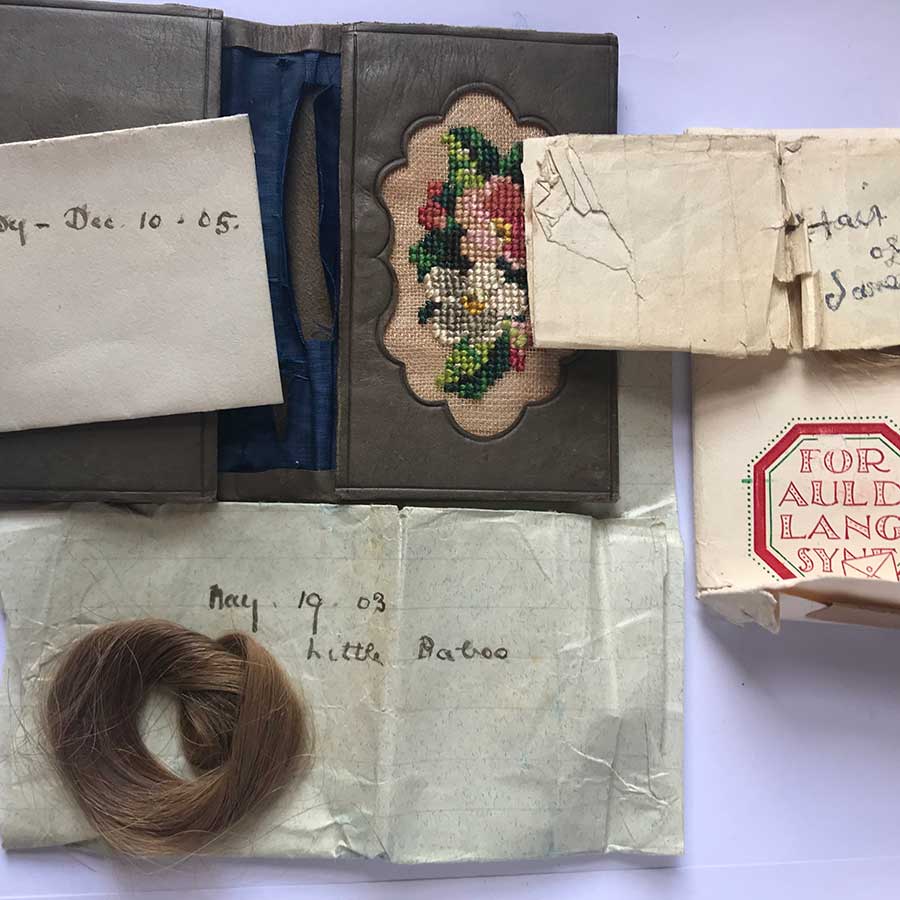

And now here I was, turning the boxes of family stuff on to their sides and tipping out their contents, so that suddenly I was surrounded by generations of family ephemera, by book marks and old scarves and diaries and Victorian christening gowns and unfinished manuscripts and poems and letters declaring love or begging for money. (There were lots of the latter.)

I began to sort and classify it by person, taking a guess at what belonged to whom, and moving things into piles on the floor. And ‘Oh,’ I said out loud, because right there I had just realised that if museums are about making meaningful patterns out of the confusions of the universe, then in what we do with our own pasts and our memories, and how we try to make sense of them, we are all museum-makers.

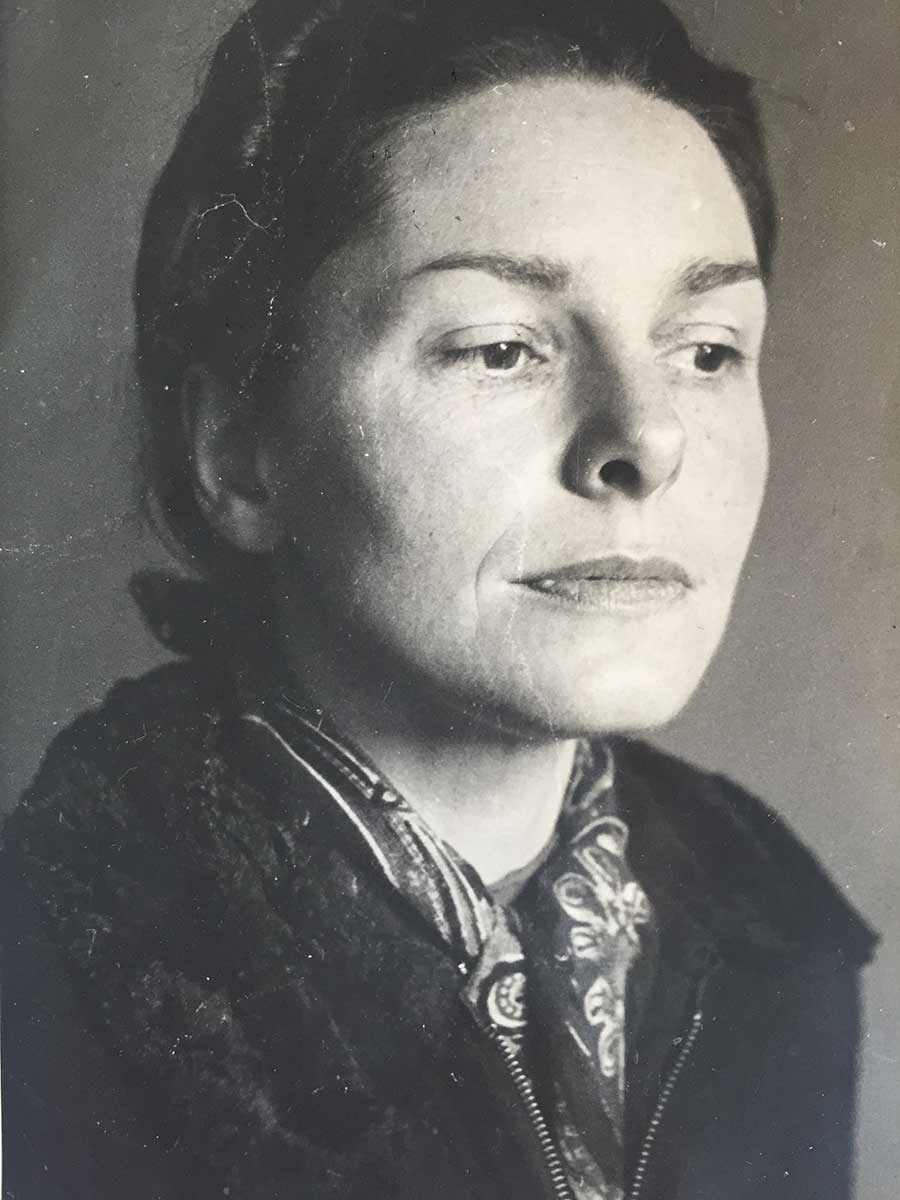

In fact I inherited two different kinds of things from my childhood. I inherited these boxes of old family stuff but I had also inherited, from the grandmother who brought me up, a collection of family stories – dark, adventurous, often tragic stories about my forebears.

My Gran mused on all these stories, half out loud, because she was trying to make sense of the things that had befallen us. But when I knelt on the attic floor surrounded by all that ephemera I was struck by something else as well, that things from the past can look nondescript and ordinary but when you connect them up to their stories they start to dance in our imaginations.

There are many historians who specialise in the history of the family and emotions. Some of what I intuited by myself as I knelt there has been said in more academic ways by these historians. They tell us that many families have, in effect, a family archive; that this archive is an important and undervalued site of meaning and identity; that women play a powerful role in maintaining a family’s culture and identity; and that they are often also in charge of the archive.

I could have written my book in a less story-ish, more academic and scholarly way, but in my mind (perhaps because of how I learnt it from Gran) it has always been a story. And so that is how the book has turned out.

I learnt many things from the process of writing this book, about time and memory and museums and family memories and the narratives that families tell, but maybe the biggest thing I learnt was, always listen to your grandma’s stories.

And if you are interested in the academic thinking round this subject, well, some of the articles and books I came across that explore these ideas include –

1. The History of Private Life’. Edited by Michelle Perrot, Harvard University press, 1990.

2. ‘We are what we keep: ‘The Family Archive’, Idenity and Public/Private Heritage.’ In Heritage and Society, Vol 10. By Anna Woodham and others.

3. ‘Inheriting the Family’ – a research network that explores the role of emotion in explaining why some objects and stories get passed down the generations.

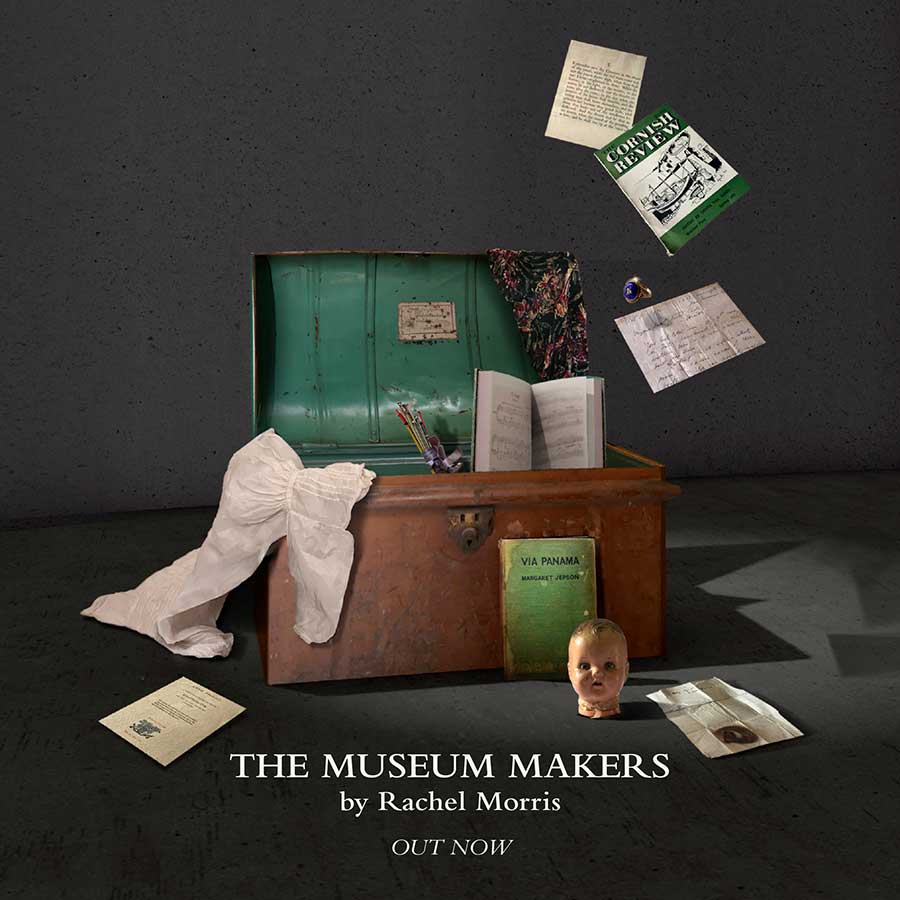

The beautiful image at the top of this article was made by the designer Su Koh.